You can't play ball with the Commies ---that's what they used to say when I was a kid growing up in a little town in the interior of British Columbia. They weren't really talking about baseball. It had more to do with Igor Gouzenko's [clerk in the Soviet Embassy in Ottawa] defection in Canada, Senator Joe McCarthy's witch hunts in the U.S., and that big shift in attitude that came with the Cold War.

But there I was, a few years later, squatting behind the plate, squinting through the bars of a catcher's mask, the sweat running down into my eyes, as Fidel Castro fired the old pelota down on me from the pitcher's mound in the sports stadium of Santiago de Cuba.

It was the summer of 1964. I was en route to London on a Commonwealth Scholarship, with a few stopovers along the way. Some weeks earlier. I had been staying with my old poetry buddy, George Bowering, in Mexico City. He and Angela had rented a little apartment on Avenida Béisbol. Baseball Street! How was I going to top that one?

I had come to Mexico to join a group of other students from various parts of Canada. We had all signed up to participate in a work project in Cuba, but there were no direct flights from Canada at that time. Two years after the Cuban Missile Crisis, and three years after the abortive US sponsored Bay of Pigs invasion, Cuba was not a popular tourist destination. However, we found the island full of students from all over the world. Some of them were studying at Cuban schools and universities, and some, like us, had come for shorter visits, invited by the government to witness the Revolution first hand, in order to counter the bad image it was getting in the Western press.

The American blockade of the island was still in effect. We could see the US warships on the horizon when we walked down the Malecon on the Havana sea front. US fighter jets buzzed the city every day or two just to shake things up, and U-2 spy planes flew high overhead. On the ground there wasn't much food or luxury, but there was great enthusiasm.

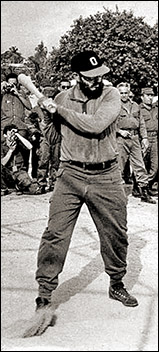

Our group spent a week in Havana and then began moving east through the island, sometimes in a green Czech bus, [visible in the background of one of the photos] sometimes in the rusty bucket of a big Russian dump truck. Other international student invitados, including a group of Americans, were doing the same kind of thing. We would meet them here and there along the way. Everywhere the Cubans welcomed us, and told us about what was happening and what they were experiencing and expecting. I was glad that I could speak a bit of Spanish.

As it turned out, we did not make it to the cane fields. Instead we spent a week doing manual labour on a school construction site in the Sierra Maestra mountains. It was not easy. It was very hot. We worked and lived side by side with the Cubans, most of them regular labourers, a few volunteers from urban areas, a few students from other countries. The menu at the camp was basic: fruits and vegetables, sausages, nothing fancy, not large rations, but enough to work on. At night we socialized and tried to get enough sleep to prepare us for the next day's exertions.

By the fourth week we had reached Santiago, Cuba's second largest city, in the eastern part of the island. We arrived in time for a traditional street carnival that coincided with the anniversary of the Fidel-led insurgent attack on the Moncada police barracks, a national holiday celebrated as the beginning of the Cuban Revolution. The carnival activity in the streets was intense, with dancers and musicians everywhere, everyone in crazy costumes.

We were staying with the other international students in the residences at the University of Santiago. One morning a jeep roared into the plaza beside the cafeteria. Something was happening. I grabbed my camera. We all crowded around. Fidel's younger brother Raúl Castro was driving, and Fidel was standing up shouting a welcome to us. Then, in English, he said:

"I understand there are some North Americans here, and I understand that North Americans think they can play baseball. Well, I challenge you to a game."

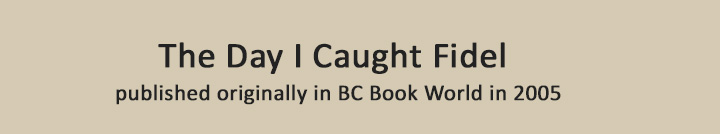

Later that day a combined team of Canadians and Americans were playing baseball. The opposition was the regular University of Santiago team with Raúl Castro inserted at second base and Fidel pitching. I was catching for the North American team.

The Cubans, of course, were much better players, and by the second inning they were far ahead. To even things up, the teams switched pitchers, with Fidel coming over to our team, and our pitcher going over to them. For the rest of the game I caught Fidel.

I had not worn catcher's equipment for a few years, but I held my mitt up there in the right place and managed to hang on to whatever Fidel threw at me. He did not have excessive speed, but he had plenty of control. His curve broke with an amazing hook, and his knuckle ball came in deceptively slow. However, he paid no attention to my signals. At one point I called time and went out to the mound to confer. I thought for sure that someone would snap our picture as I stood there in my dusty catcher's outfit, glove in one hand, mask in the other, while Fidel told me, quietly, "Hoy, los signales no están importantes."; Apparently he did not take direction from other people, not even from his catcher. And as far as I know, that photo, famous only in my imagination, was never snapped. Even so, with Fidel's help, our team managed to hold down the opposition to one or two more runs.

Near the end of the game Che Guevara put in an appearance. He stood there in his olive green fatigues, smoked a cigar, and watched. As an Argentinean, he was not such a committed baseball aficionado.

I had once seen a CBC television documentary on Cuba that featured Che extolling the theory and practice of voluntary labour. The camera had caught him standing amidst the high cane, machete in hand, answering the interview questions in halting English. Che had defined Socialism as the abolition of the exploitation of one person by another. That had made a lot of sense to me. I too was ready to swing a machete in the tropical sun to further such ideals. In fact, that was the reason I had applied to come on this student work visit to Cuba. I had not guessed that Che would be standing over by the dugout watching me play baseball with his pal Fidel.

The night before the game I had been in the bleachers of this same stadium watching the Cuban National Ballet performing Coppelia. The day after the game I would listen to Fidel make an impassioned four hour speech to a throng of almost a million people standing and cheering in the 98 degree sun. At the end, we would all link arms and sing The Internationale.

A few years after that game in Cuba, I was back in Vancouver playing ball with George Bowering on the infamous Granville Grange Zephyrs, scourge of the Kosmic League. But that is a tale for another day.

The Granville Grange Zephyrs

Back (L-R) - Brad Robinson, Gary Nairn, Glen Toppings, Coach unnamed, George Bowering, Lionel Kearns, Dennis Vance.

Front - Gerry Nairn, Dwight Gardener, Brian Fisher, Lanny Beckman. Bat Boys: Liam Kearns, Frank Kearns.